AeroTime columnist Renato Oliveira is Operations Director at PVJets Global Private Jets Company, which specializes in charter flights and helicopter transfers for entrepreneurs, individuals, families, and groups.

Renato spent 15 years as Senior Cabin Crew in the Middle East and has a lifelong passion for aviation history. He has also led the largest research project on Alberto Santos-Dumont and was condecorated by the Brazilian Air Force for efforts in aviation preservation.

Renato is now working to shape the future of private aviation, connecting today’s innovators with tomorrow’s history.

The views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of AeroTime.

Today, the great gatherings of aviation and aerospace such as Farnborough in England, Le Bourget in France, Dubai, Singapore and Oshkosh in the United States, are stages where the latest aircraft, engines and technologies are unveiled to the world. These fairs feel inseparable from the roar of runways and the spectacle of flying displays. Yet the birthplace of this tradition was not an airport at all. The roots of every air show and aerospace exhibition lie beneath the monumental glass vaults of Paris’s Grand Palais, a building raised for art and industry at the dawn of the 20th century and still standing as a silent witness to the birth of global aeronautics.

At the beginning of that century, the dream of leaving the ground had already leapt from fantasy into reality. Balloons had carried explorers aloft for more than a hundred years, dirigibles were beginning to stretch their range, and heavier-than-air machines had finally proven themselves capable of sustained, controlled flight. What was missing was a stage to display these marvels, a place where inventors, pilots, industrialists and the curious public could gather under one roof. Paris offered the stage, and the Grand Palais became the theater.

The first aeronautical exhibition of 1908

The building itself had been created for the Exposition Universelle of 1900. Just a few years later, it was nearly condemned to demolition; its vast iron skeleton and glass roof dismissed as an extravagant relic of the past. But instead of vanishing, it was given a new purpose. In December 1908, the Grand Palais hosted the very first aeronautical exhibition in history. What had once been built to honor the arts and industry of the 19th century suddenly became the cathedral of the 20th, the house of flight.

The idea came from Robert Esnault-Pelterie, the brilliant inventor of the joystick and one of the earliest monoplane designers, together with André Granet, architect and nephew of Gustave Eiffel. They had recently founded the Association des Industriels de l’Aéronautique and were determined to give French aviation a stage worthy of its achievements. Their opportunity came when the Grand Palais hosted the Paris Automobile Salon. In one corner, alongside cars, they installed a new wonder: flying machines.

Pioneers under glass

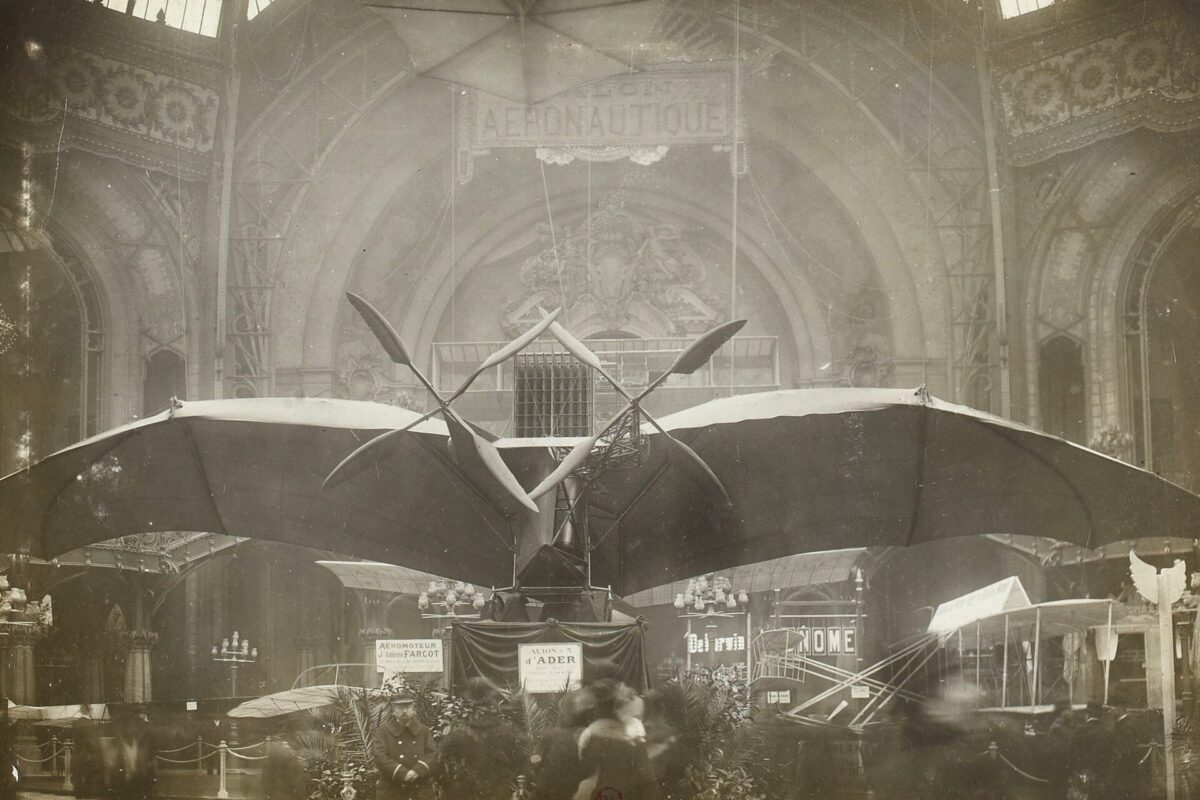

Visitors who entered the palace in December 1908 were greeted by Clément Ader’s Avion, defiantly placed opposite the entrance as a reminder of France’s early claim to controlled flight. Just beyond stood Henri Farman’s Voisin biplane, fresh from its kilometer record the previous winter. Louis Blériot presented three machines, the Blériot VIII, IX and X, while Esnault-Pelterie showed his elegant steel-tube monoplane and its engine. Astra displayed the Wright brothers’ biplane, proof that the Americans too had mastered the air. The Breguet brothers unveiled their experimental gyroplane, a forerunner of the helicopter. And among these giants of wood and canvas appeared the Demoiselle, designed by Alberto Santos-Dumont but exhibited by the industrialist Clément-Bayard, who had begun to manufacture and promote it. It was a tiny dragonfly of an aircraft, hinting at the possibility of a personal flight. Suspended nearby were models and gondolas of dirigibles from Astra, Zodiac and Clément-Bayard, reminders that lighter-than-air craft still held pride in place.

The section that most astonished visitors, however, was the gallery of engines. For the first time, the public could touch the beating hearts of flight: the Antoinette V8 and V16, finely engineered; the Anzani radial, soon to carry Blériot across the English Channel; Renault’s novel air-cooled engines; and the revolutionary Gnome rotary, the first lightweight engine to run reliably. Here, perhaps more than in the display of fragile aircraft, the transformation of aviation from curiosity into industry could be felt.

Those present in 1908 formed a pantheon: Clément Ader, Alberto Santos-Dumont, Henri Farman, Louis Blériot, Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Gabriel Voisin, Louis and Jacques Breguet, Léon Levavasseur, Maurice Mallet, Maurice Clément-Bayard and André Granet. With them, and under the Grand Palais’s great dome, aviation became not just an invention but a movement, a community, and a market.

The experiment quickly became a tradition. In 1909, the Grand Palais hosted the first international exhibition devoted exclusively to aviation. More than 380 exhibitors filled its glass halls, and 100,000 visitors streamed through the doors. Blériot’s Type XI, which had crossed the Channel only weeks before, was the centerpiece. Farman’s biplane stood beside it, fresh from its world endurance record, and the Wright biplane of the Comte de Lambert would soon after circle the Eiffel Tower. For the first time, sections were dedicated to meteorology, physiology of flight and aerial photography, signs that aviation was already reaching beyond sport into science and society.

Innovation and aviation fever

The years that followed were a whirlwind. In 1910, the crowd marveled at Henri Coandă’s experimental jet biplane and Henri Fabre’s hydro-aeroplane, the first seaplane. By 1911, aircraft were being shown armed, and Blériot presented a “Berline” designed for passenger transport across the Channel. Even Louis Vuitton, together with his brother, presented their own flying designs, proof that the fascination with flight extended far beyond engineers and pilots to touch fashion houses and industrial dynasties alike. In those years, aviation fever gripped Paris so completely that everyone with imagination, resources or ambition sought to be part of it.

In 1912, war’s shadow grew long. Planes fitted with machine guns and bomb racks were openly displayed, and competitions tested bombing accuracy. In 1913, on the eve of the Great War, the Grand Palais was filled with 34 aircraft and nearly a hundred engines. The optimism of 1908 had turned into preparation for conflict.

Postwar rebirth and commercial promise

When the salons resumed in 1919, the world changed. The palace now displayed bombers reimagined as airliners, the Farman Goliath, Blériot Mammouth and Caudron C-23. More than 270,000 visitors came, drawn by the promise of commercial air travel. By 1921, the exhibition was officially called the Salon de l’Aéronautique, and the future was on display in René Tampier’s folding-wing car-plane and the Pescara helicopter with contra-rotating blades. Dioramas mapped out planned air routes across Europe, the Middle East and Africa, reflecting France’s ambition to dominate global skies. In 1922 and 1923, more than 250,000 visitors admired 42 aircraft and the mighty Napier CUB engine, a 1,000-horsepower marvel that symbolized the new scale of aviation.

From that modest corner display in 1908 to the massive postwar shows of the 1920s, the Grand Palais had become more than an exhibition hall. It was the nest where modern aviation hatched. Beneath its glass vaults, fragile wood-and-fabric contraptions gave way to metal monoplanes; sport became industry, industry became strategy, and strategy turned into commerce. The Grand Palais was not simply saved from demolition by an exhibition. It became the birthplace of global aeronautics, the nest of evolution that would guide the world for the next centuries.