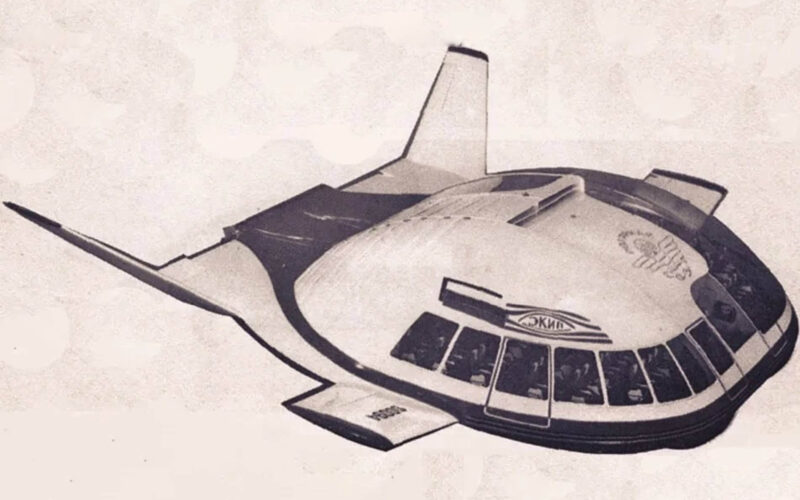

At one point in history there was an aircraft that could take off and land without an airport, despite being the size of Boeing 747 jumbo jet. It used eight times less fuel and was twice cheaper than any conventional airplane. It was also completely immune to crashes, and looked like something from 80s sci-fi movies.

It was the EKIP: the Russian flying saucer. The transport of the future that never was.

What a future that could have been, though. If one was to believe everything written about the project – a difficult task, as half of the information contradicts the other half – the EKIP is one of those technologies that could have revolutionized everything on the planet. Think nuclear fusion reactor, plus EmDrive, multiplied by Brunelli lifting fuselage. Yes, it goes that deep.

The actual facts are difficult to discern, lost in the mist of time, propaganda, advertisements, media sensationalism, and untamed excitement of some of the world’s craziest conspiracy theorists. But at least part of the truth can be siphoned from it, revealing a gripping story of (alleged) inventiveness, (alleged) espionage and (alleged) corruption.

The beginning

The story starts, and for the most part ends with engineer Lev Nikolayevich Schukin. If his contemporaries and associates are to be believed, the man – till his last days in 2001 – believed in the uniqueness and the immense potential of inventions he proposed.

Schukin started his career at Energia design bureau, where he had a chance to work on the ill-fated N1, the super heavy rocket designed to rival NASA’s Saturn V. According to some accounts, he left after the collapse of the Soviet Moon program and the subsequent turbulent change of Energia’s leadership. According to others, he stayed there a little more, and played an important role in the Apollo-Soyuz mission.

Then there was a period of working on hovercraft, an experience which could have heavily influenced the upcoming EKIP. By the late 70s, Schukin starts having his own ideas about a completely new type of transport, and offering them to the leadership. In 1979 he gets a permission to form a separate bureau for the development of his unique project.

The project was named “EKIP”, a very Soviet, but at the same time quite uncharacteristic acronym of “ecology and progress”. Ecology – as in, the new aircraft will be more environmentally friendly than anything before. Progress, as in it is the future.

The list

The idea was to include a whole slew of very innovative, very unproven ideas into one airframe, leapfrogging any competing developments of prospective vehicles.

The airplane – if such a name can be used at all – would be a variation of a flying wing, something that always was futuristic in itself, no matter the context. In theory, aircraft of this type can be more efficient than classic tube-and-wings designs, as they don’t have parts that generate drag without generating lift.

Flying wings are notoriously difficult to fly though, so, a new heavily computerized control system had to be devised. There is very little information on this development, but it alone was a significant part of EKIP’s innovativeness.

Conventional airplanes need a lot of infrastructure to function, hence, large and expensive airports have to be built and maintained. An aircraft of the future had to do away with that, landing on air cushion, like a hovercraft. But mechanisms for that are heavy and complicated, and especially awkward to fit on a flying wing-type aircraft. The shape has to be suitable for the installation of a cushion, and if the internal cargo hold or passenger cabin is to be made spacious and comfortable (a prerequisite for the aircraft of the future), the airframe has to be rather bulky.

Bulkiness means a lot of drag. A contraption to solve that issue has to be devised, in the form of boundary-layer control mechanism that spits the air out of the aircraft’s back. In theory, that could prevent forming of vortices that slow the vehicle down. In practice, developing a working boundary-layer control system requires calculations that computers from the 80s have nightmares about.

Oh, the fuel in our aircraft of the future can’t be regular too – the “EK” part of the name isn’t there just for show. A new jet engine has to be devised that could consume not only jet fuel, but hydrogen and natural gas too. It would even accept aquazine, amix of water and waste products of gas industry – a “wonder fuel” developed by soviet chemists at the time, and a subject of many a conspiracy theory since then.

Yet another innovation the designers proposed, a set of highly efficient high-bypass turbofans with noise reduction features, looks rather tame in this context.

The gaps

From this list alone one can imagine the hopes put into the project. Schukin quickly gathered a team of able and loyal engineers, but the work was hard and slow. The sheer amount of cutting-edge developments made it an all-encompassing effort much of the Soviet aircraft industry could have worked on, and according some accounts, it did. Supposedly, scientists from Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI), Energyia, and half a dozen other Soviet constructor bureaus were attached.

Yet the situation is very unclear. In almost all accounts, there is a gap between 1982, when the first prototype was constructed, and the late 80s, when the work on the second prototype started. There is no documentation, no names, no data. All the footage of wind tunnel tests at TsAGI was filmed in the early 90s, so, there is a chance that the project spent quite a lot of time on hold.

Why? Various reasons might have contributed to that. It is possible that Schukin’s development was not taken very seriously by the leadership, for being either too unconventional, or too expensive, or not too realistic. Its breakthrough happened after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the climate for radical ideas was perfect.

Whatever really happened, the capitalist makeover sunk almost all scientific developments from the Soviet era, but offered immense opportunities for those scientists who could adapt.

Schukin created the EKIP Aviation Concern, and started advertising to the West.