On this day, 40 years ago, Air Florida Flight 90 was preparing to depart Washington D.C. en route to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The aircraft, a Boeing 737-200, was loaded with 74 passengers, including three infants and five crew. The flight was due to depart at 14:15, but prolonged heavy snowfall, accompanied by subfreezing temperatures of minus five degrees, temporarily closed the airport, resulting in a backlog of arrivals and departures.

At 15:35hrs, after several delays and 1.45 hours late, the flight was pushed back and taxied to runway 36 where it was cleared to take-off with no further delay. Once rolling, the First Officer, who was piloting the plane, made several comments to indicate that instrument readings did not match the performance of the plane. Despite these concerns, the crew continued with the take-off.

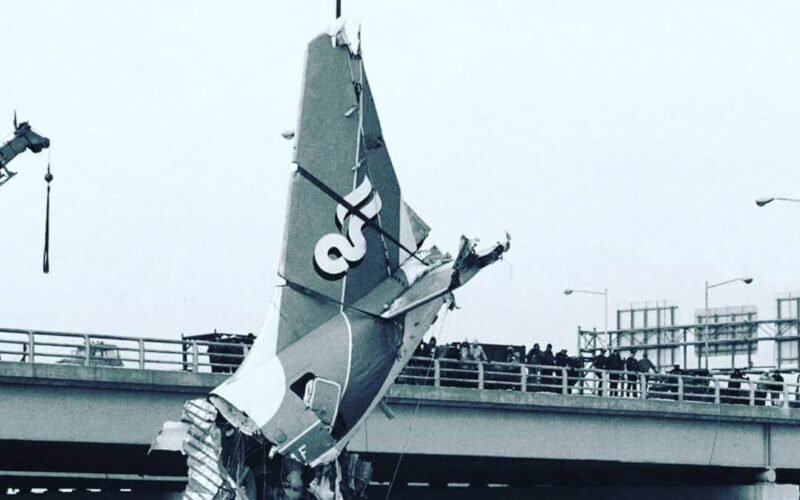

On rotation and climb out, the aircraft began to pitch up, speed began to bleed off and the stick-shaker activated. At 16:01hrs, just 30 seconds after becoming airborne, the aircraft struck the heavily congested 14th Street Bridge, ploughing into seven vehicles before plunging into the ice-covered Potomac River.

In the moments following the crash, six survivors managed to escape the wreckage and await rescue. While nearby civilians and emergency services attempted to rescue the survivors, their efforts were hampered by the sheer volume of ice in the river, which had rendered boats useless. Within 20 minutes, a U.S. Park Police helicopter arrived at the scene and began to skillfully hover inches above the water while a crew member passed a rope to the now hypothermic survivors.

One of the survivors in the water, Arland Williams, began to selflessly pass and secure the rope around four other people. Sadly, Williams drowned before he could be rescued. Bystander Lenny Skutnik dived into the water, managing to rescue passenger Priscilla Tirado and bring her to shore.

Of the 79 souls on board, only five would survive. The horrific circumstances of the crash tragically claimed the lives of a further four people, who received fatal injuries when the aircraft slammed into the bridge. On that wintery afternoon a total of 83 perished.

In a further blow to the city, a nearby train derailment, separate to the plane crash, killed three people on the same day. January 13, 1982, proved to be a dark day in the history of Washington D.C.

What went wrong?

1. De-icing and contaminated surfaces:

During cold weather operations, ice and snow can build up on the surfaces of aircraft. This accretion can lead to disrupted airflow, increased weight, and increased drag, particularly over the wings. All this leads to a reduction in lift, and higher stall speeds. To counter this, aircraft undergo de-icing.

The investigation concluded that although de-icing had been carried out, there were several errors and lapses in the procedure.

In contradiction to the airline’s procedures, the highly sensitive pitot tubes, static ports, and engine inlet sensors were all left exposed during the de-icing. Additionally, equipment used in the procedure was found to dispense a weaker than appropriate de-icing fluid concentration for the prevailing conditions, reducing its known effectiveness.

Finally, the delay of almost 50 minutes between the de-icing and take-off, allowed a fresh build-up of snow and ice to accumulate on the aircraft. Unfortunately, despite their responsibility to do so, neither the maintenance personnel, nor the Captain inspected the aircraft for signs of any remaining snow or ice presence before pushback and taxi.

2. Blockage of the Engine pressure ratio (EPR) sensor:

Recovery of the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and its subsequent analysis showed that during the take-off roll the First Officer made four comments about the instrument readings not matching the throttle position and aircraft performance. Unfortunately, despite these doubts, the Captain decided against the option of rejecting the take-off.

The investigation discovered these erroneous readings were due to blocked engine sensors. This led the crew to unknowingly select a lower than required thrust setting for take-off. It equated to roughly 3750 pounds less thrust per engine than required for the conditions. The aircraft took 15 seconds and 2000ft of extra runway to reach its lift-off speed.

What caused the blockage?

Witness statements and the cockpit data recorder (CDR) revealed several pieces of information. While on the stand, due to the tug being unable to push the aircraft in the snow and ice, the crew elected against company policy to use reverse thrust to help move the aircraft off the stand. The attempt was unsuccessful and most likely contributed to ice accretion, which was the result of the jet blast spraying slush into the engines and onto the surfaces of the aircraft. This would have subsequently frozen.

Moreover, the CVR noted discussions between the First Officer and the Captain indicating that they were both aware of slush or snow present on the wings while waiting for clearance to take-off. The crew decided to maneuver the aircraft close to the preceding aircraft to use its exhaust gas heat and jet blast to remove snow and ice from the wings. It is likely that this led to further blockages in vital sensors as well as worsening the ice and snow build-up on the airframe.

Despite this attempt, the crew were recorded still sighting “a quarter to half an inch [of snow] on it [wing] all the way”. No attempt was made to undergo a second thorough de-icing.

3. Engine anti-ice:

During the after-start checklist, the CVR revealed that when the Captain was prompted “Engine Anti-ice?”, he simply replied “Off”. While taxiing, the First Officer noted sharp contrasts in instrument readings indicative of engine icing, but the subject was never discussed again.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) concluded that turning the engine anti-ice off was a direct cause of the accident.

Take-off:

The final opportunity to prevent the disaster presented itself on the take-off roll. During the take-off there were four occasions when the First Officer questioned the reliability of the instruments. Within 10 seconds of applying power, he stated: “That doesn’t seem right, does it?”, followed by “Ah, that’s not right”. The captain replied: “Yes, it is, there’s 80,” referring to the speed, but the First Officer again expressed concern: “Naw, I don’t think that’s right,” he said. There was no response from the Captain.

The take-off continued, and the flight, with a fatal combination of ice or snow contamination on the airframe and lower than required thrust, sealed its fate. It is believed that neither of these factors alone would have been enough to cause the accident.

Other factors:

The NTSB concluded the actions of the pilots on the day of the crash could be attributed to their lack of experience in winter jet-aircraft operations. This is further cemented by their lack of knowledge of the systems and the effects of icing conditions. It was also evident that faced with the delays, the crew would have attempted to expedite their departure at the expense of safety. Air Florida operating manuals also stated that a rejected take-off was the sole responsibility of the Captain.

Outcomes:

Holdover time (HOT) tables are now used to advise crew on how much time can elapse without the need to de-ice again, based on the de-icing fluid used and the weather conditions.

The FAA required airports with significant flight paths over water to meet new rescue capabilities, with emphasis on rescue equipment suitable for the weather conditions the airport could expect year-round.

Today, Crew Resource Management (CRM) training is incorporated into flight training and teaches pilots how to raise flight issues with the Captain. In the case of Flight 90, the Captain neither listened to or acted upon the concerns of his First Officers. Current models such as RAISE use persuasive language to hint and suggest action, with different tiers of increasing severity. If no appropriate action is taken by the Captain, the solution is to take control of the aircraft.

Air Florida filed for bankruptcy in July 1984.

There is no doubt that without the swift response of the nearby helicopter crew and the fast action of bystanders, the few passengers who managed to survive the crash would have perished. The heroism displayed that day was highly commended and the 14th Street Bridge was later renamed the Arland D. Williams Jr. Memorial Bridge.