On this day eight years ago, Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 left Kuala Lumper International Airport at 00:42 MYT (16:41 UTC) bound for Beijing, China. The aircraft, a Boeing 777-200ER, was loaded with 239 people, comprising 227 passengers and 12 crew with an expected flight time of five and a half hours.

At 01:19 MYT, 38 minutes after takeoff, MH370 reached cruising Flight Level 350 (approximately 35,000ft) over the South China Sea. As the aircraft approached the border of the Vietnamese Flight Information Region (FIR), Kuala Lumper air traffic control (ATC) instructed the crew to contact Ho Chi Minh ATC. The captain of MH370 replied “Good night, Malaysia Three Seven Zero”. These were the last words transmitted from the aircraft. Less than 60 seconds later the Boeing 777 disappeared from civilian radar.

As the minutes unfolded with no sign nor sound from MH370, Ho Chi Minh ATC attempted to contact Flight 370, using other aircraft in the vicinity to relay messages. But only a single reply of mumbling and radio static was heard. Malaysia Airlines operations, having been informed of the unfolding events, attempted twice to call the flight deck via satellite link, but the calls went unanswered.

As the elapsed flight time reached 05:48, Flight 370 missed its scheduled arrival into Beijing, and a rescue coordination was activated from Kuala Lumper. With the flight duration approaching seven hours, Malaysia Airlines issued a press release announcing that Flight MH370 was missing. The aircraft had departed with fuel to allow a total flight endurance of 07hr 31min.

At the time, the disappearance the deadliest incident involving a Boeing 777, and what followed was one of the biggest and most expensive multi-national search operations in history. The fact that a modern airliner could simply vanish shook the world, and would set Malaysia Airlines on course for a truly tragic year.

The search

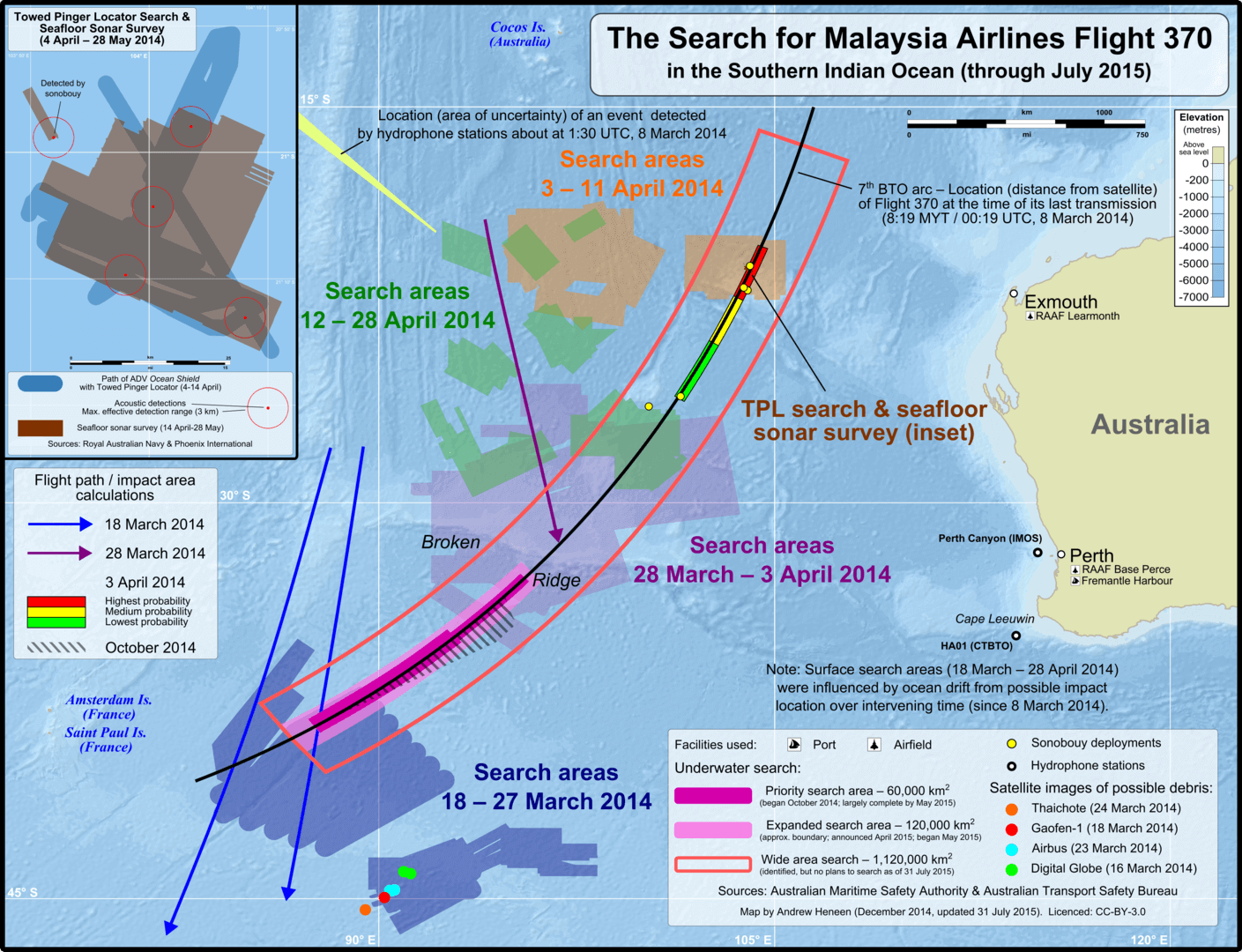

In the hours after the disappearance, the search effort was focused in the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand where contact was lost with ATC. However, in the days that followed, the military disclosed that the aircraft had been spotted on military radar and, almost immediately after disappearing from civilian radar, the aircraft had made a left turn back towards Malaysia and over the island of Penang. The aircraft last appeared on radar approximately 370km to the north west of Penang before dropping from military radar coverage.

Image: Andrew Heneen, CC BY 3.0

‘Handshakes’

The most significant and damning turn for the investigation came from the British satellite network Inmarsat which, having analyzed data exchanged between MH370 and satellites, determined that the aircraft had flown for a further six hours following its final sighting on radar. This information was made public on March 14, 2014.

The data came from what is known as a ‘handshake’ between an aircraft and a ground station (e.g. satellite dish) via satellites in orbit. Every hour a ‘handshake’ is initiated by either the ground station or the aircraft. In the case of MH370, a total of seven of these ‘handshakes’ occurred following the final radar sighting.

The final handshake was recorded at 00:19’29” UTC (08:19’29” MYT) while the following hour at 01:15’ UTC (09:15’ MYT) three ‘handshake’ attempts by a ground station went without a response from MH370.

Following the Air France 447 disappearance and a lengthy search operation in the Atlantic Ocean in 2009, Inmarsat upgraded several ground stations to enable more data to be recorded and stored from these handshakes, allowing for the distance to be measured between a satellite and an aircraft.

The information captured from these handshakes allowed Inmarsat to plot a flight path for the aircraft. It concluded that the final handshake from MH370 positioned the aircraft on a ‘7th arc’ over the southern Indian Ocean west of Australia.

The possible search area is more 1,120,000 square kilometres with ocean floor depth of over 5,000 meters. Australia, whose waters the search area lies within, began searching on March 17, 2014.

The rescue now focused on finding the aircraft by listening out for underwater locater beacons (ULBs) which ping on a set frequency. The ULBs have a battery life of around 30 to 40 days and, as the 40th day passed with no positive identification of the pings, the chances of finding the aircraft were significantly reduced.

Image: Andrew Heneen, CC BY 3.0

Further developments

Tragically, on July 17, 2014, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumper, was shot down by a surface-to-air missile over Ukraine, killing all 298 passengers and crew on board. The shocking incident overtook MH370 as the most deadly Boeing 777 incident.

In July 2015, a piece of debris was found washed up on a beach on Réunion, a French island in the western Indian Ocean. It was a flaperon – part of the control surfaces of the wing – and was determined to be from the right wing of MH370. Further examination, including other found debris, has allowed investigators to conclude that the aircraft was not configured for a water ditching at the end of its flight.

On January 17, 2017, 1,046 days on from the incident, the official search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 was suspended. Some 661 areas of interest were flagged following sonar imagery of the seafloor, and 82 were thoroughly searched and eliminated with no sign of the aircraft. Despite lengthy surface and underwater searches, nothing relating to MH370 has yet been found along the 7th arc.

Image: Andrew Heneen, CC BY 4.0

Outcomes

To date, MH370 has not been found, nor has any conclusion been made as to what led to the aircraft’s disappearance. But it is widely accepted that the Boeing 777 aircraft suffered from fuel exhaustion in its final moments of flight.

The story of MH370 continues and has served to prompt many changes within the industry relating to aircraft tracking and search and rescue ability.

Flight recorders on aircraft manufactured after 2020 are required to record at least 25 hours of data to ensure that all phases of flight are noted. In the case of MH370, the flight recorders were only capable of recording two hours, constantly recording and re-writing over data. So, if they are ever found, little will be known about the crucial events on the flight deck 38 minutes after takeoff when the last radio transmission was made.

EASA (European Aviation Safety Agency) also issued new regulations stating that underwater locator beacons (ULBs) fitted to aircraft which transmit an electric pulse must be able to transmit for at least 90 days, an increase from the previous minimum 30-day regulation.

From November 2018, all aircraft flying over open ocean are required to report their position every 15 minutes. Furthermore, aircraft manufactured after January 1, 2021 are required to have auto-tracking devices installed, capable of sending location information at least once per minute.

Meanwhile, Inmarsat has changed the intervals between handshakes from 1 hour to every 15 minutes.

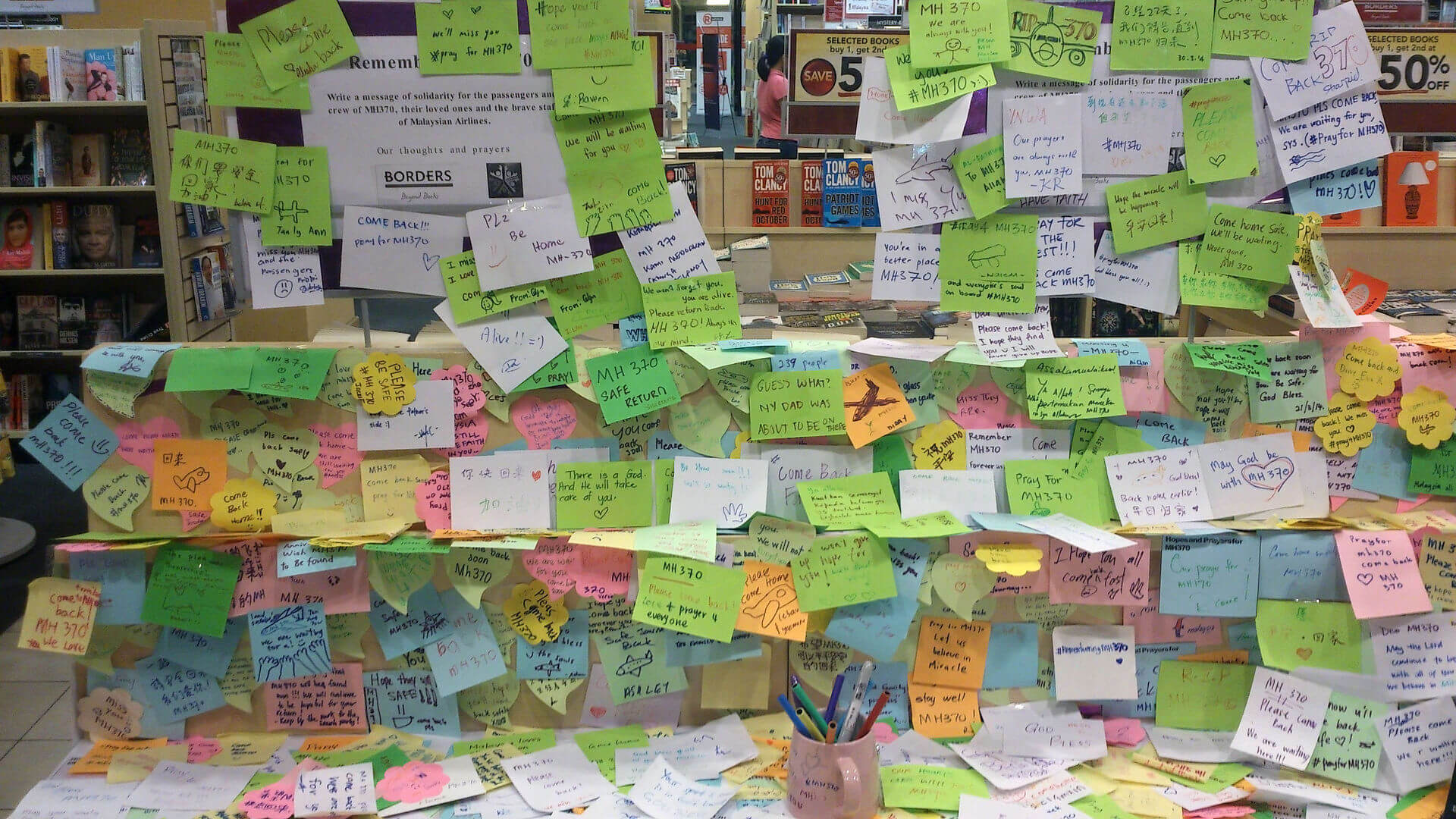

For the victims’ families, the disappearance of Flight MH370 is much more than an aviation mystery – it’s the irreplaceable loss of loved ones. We must always remember that 239 people vanished with no trace and no explanation. The horrific circumstances from eight long years ago have meant no closure and very limited information about the final moments of the lives of everyone on board.

We can only hope that, by improving practices and technologies, no such event ever occurs again, and perhaps one day the final resting place of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 will be discovered bringing answers and resolution to a terrible chapter in aviation.

Image: WikiMedia, CC BY-SA 3.0