Airline consolidation, mergers and acquisitions have often resulted from a global economic shift and by a need to stimulate growth within an airline business.

From 2000-2010, the US airline market consolidated to four airlines following the economic conditions that occurred in the wake of the dot-com bubble burst, the 9/11 terrorist attacks and The Great Recession.

Across the Atlantic, consolidation in the European airline market has moved at a much slower pace despite the presence of large-scale legacy airlines and low-cost carriers (LLCs).

However, following a two-year downturn in traffic during the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the unexpected resurgence of travel demand and the lack of capacity to satisfy that demand, is the European airline market in line for further consolidation? AeroTime investigates.

Europe’s airline market

A select group of legacy and low-cost carriers have gained a significant market share of European passengers over the past two decades. This mainly includes airlines such as Air-France KLM, International Airlines Group (IAG) (IAG), Lufthansa (LHAB) (LHA), Ryanair, EasyJet and Wizz Air.

The Air France-KLM merger, which took place on May 5, 2004, rekindled European airline’s interest in consolidation. The Air France-KLM group, whose fleet currently comprises 554 aircraft, also owns low-cost subsidiary airlines Transavia Hop and Martinair.

International Airlines Group (IAG) (IAG) was formed in 2011 following a merger between British Airways and Iberia. IAG operates as the Spanish-registered parent company of its group of airlines with a fleet comprising 531 aircraft.

The IAG group consists of airlines such as British Midland Airways and Iberia Express (both acquired in 2012), Vueling and Aer Lingus (acquired in 2013 and 2015 respectively), its low-cost long-haul airline brand LEVEL (established in 2017), and its cargo brand IAG Cargo.

In 2019, IAG sought to expand its operations in Madrid, Spain, announcing its intent to acquire Air Europa in a deal valued at $1.1 billion.

Air Europa is the third largest Spanish airline behind Iberia and Vueling. Combined, the three airlines account for 84% of the domestic seats in Spain, according to 2019 data. The acquisition would effectively consolidate Spain’s domestic market to IAG airlines.

Dating back to as early as 1926, Lufthansa Group is one of the oldest of Europe’s legacy carriers. The group operates as a traditional company, which differs from the model of a holding company which exists solely for the ownership of the assets of its subsidiaries, as seen with Air France-KLM and IAG.

Across its three main business segments – Network Airlines, Eurowings and Aviation Services – the group’s airlines consist of Lufthansa (LHAB) (LHA), Austrian Airlines, Swiss International Air Lines, Eurowings, Eurowings Discover, Brussels Airlines, and Germanwings

As of March 31, 2022, the Lufthansa Group’s fleet comprises 710 aircraft, making it the largest airline group in Europe by fleet size.

Resurgence in travel demand causes operational issues

Global demand for air travel has returned faster than expected, outpacing the industry’s ability to allocate the needed aircraft capacity.

In its latest market forecast, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) forecasted that passenger numbers are expected to reach 83% of pre-pandemic levels in 2022. The association also projected that the industry would lose $9.7 billion in 2022, revised from its previous forecast in October 2021 of $11.6 billion.

While the surge in passenger demand is a good indicator that the industry is continuing its post-pandemic recovery, airlines are still facing a perfect storm of concerns that are significantly impacting daily operations. These can be narrowed down to capacity constraints, high fuel costs and personnel shortages.

“This major aviation crisis has created the conditions for a greater consolidation process in the European market. From the market’s perspective, it may seem like anticipated development for European carriers. However, it’s not as simple as that.” – Vygaudas Ušackas, Member of the Board of Directors at Avia Solutions Group

Can a consolidated Europe be compared to the US airline market?

While European airlines operate under a single market, their airspace is more fragmented, leading to less profitability compared to North American airlines, which operate under one domestic market.

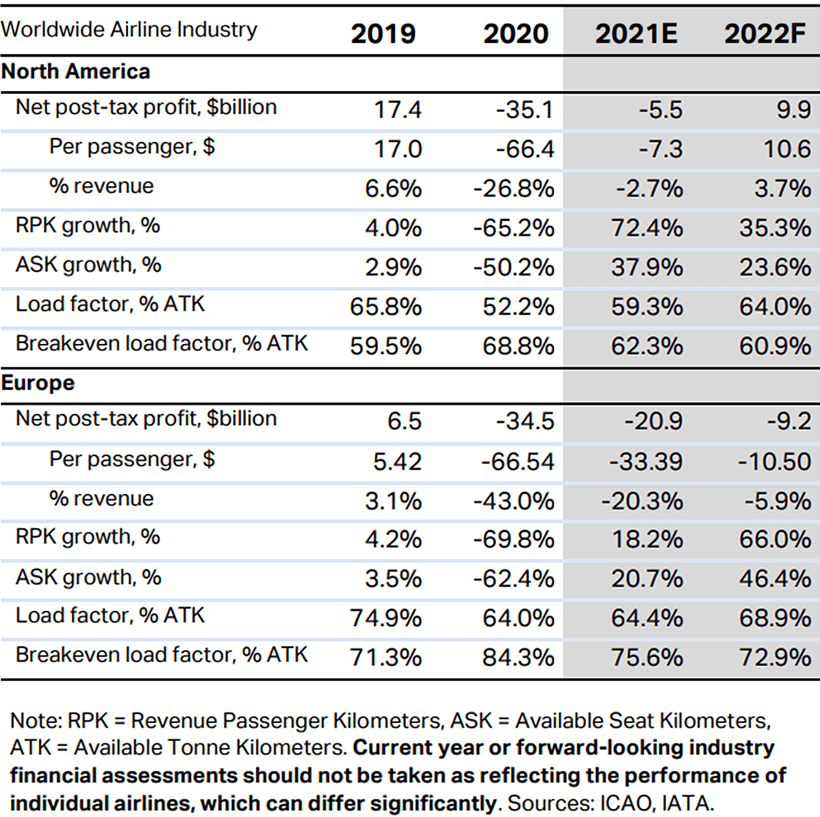

Economic Performance of the Airline Industry: Regional financial performance. Source IATA

According to the IATA’s most recent economic forecast, the airline industry in North America recorded a net post-tax profit of $17.4 billion against Europe’s $6.5 billion in 2019. The North American airline industry is also expected to be the first and only region to record a net industry profit ($9.9 billion) in 2022.

Vygaudas Ušackas, Member of the Board of Directors at Avia Solutions Group, a provider of end-to-end capacity solutions for passenger and cargo airlines worldwide, spoke to AeroTime about the current conditions in the industry and their potential to stimulate further consolidation for European airlines.

“If we were to compare what the US carriers went through a couple of decades ago, the environment seems very similar. Put the pandemic, mass personnel layoffs during COVID on top, and pair it with the pandemic after-effects of high fuel costs, flight disruptions, and global recession, and you have a perfect mix for Europe’s ‘great consolidation’,” Ušackas said.

“This major aviation crisis has created the conditions for a greater consolidation process in the European market. From the market’s perspective, it may seem like anticipated development for European carriers. However, it’s not as simple as that,” Ušackas added.

According to a 2018 report by Oliver Wyman, the top five intra-North American carriers commanded a 77% market share in 2018 versus a 51% market share for the top five intra-European airlines.

“The top US carriers are bigger, and smaller shares of their traffic are international because the US is so much bigger than any single EU country. In addition, intra-EU connecting passengers are less important than in the US, given that the old flag carriers flew nonstop to the other European capitals, as do their descendants,” Jan K. Brueckner, Professor of Economics at the University of California and airline merger expert, told AeroTime.

This is an idea touched upon by Ušackas as he highlighted disparities in domestic commercial airline competition between the EU and US airline markets.

“The US market is much more liberal. Costs, the number of airlines in the market, consolidation laws, and product quality are only a few examples of that. There’s also the fact that airlines in Europe carry a heavier burden in terms of a country’s financial dependency on them,” Ušackas said.

“Alongside that, when competition is minimal and an oligopoly-like situation is present like we see in the US, the airlines dominating the market have greater control over price. As a result, US mainstream carriers have been challenging each other for the majority of market profits. In the EU this type of situation is much rarer. Airfares are largely more expensive per seat mile in America than in Europe and, on top of that, the final fare paid by the consumer includes taxes,” he added.

While each of Europe’s legacy airline groups hold what is referred to as a ‘golden share’ (controlling at least 51% of voting rights, a company or market) within their home market, Brueckner argued that what separates US and EU legacy carriers is subject to national interests.

“A big difference between consolidated European airlines and those in the US is the maintenance of the pre-consolidation brands (e.g., BA and Iberia, Air France and KLM). Evidently, it’s a matter of national pride, which would be injured by the disappearance of the flag carriers’ brands,” Brueckner explained.

For Ušackas, a key point is that European governments are reluctant to allow national carriers to “simply disappear” and will continue to support them “even if the airline is unprofitable”.

“In turn, European airlines’ consolidation will most likely be a longer-term process than what we saw in the US a couple of decades ago,” Ušackas added.

“A big difference between consolidated European airlines and those in the US is the maintenance of the pre-consolidation brands. Evidently, it’s a matter of national pride, which would be injured by the disappearance of the flag carriers’ brands.” - Jan K. Brueckner, Professor of Economics at the University of California and airline merger expert

Disproportionate government support

In late March 2020, a support package of $50 billion was set aside by the US Congress to assist the country’s airlines following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Across the Atlantic, European governments agreed to almost €38 billion in financial aid for airlines by the middle of 2021, with the potential to receive an additional €4 billion.

“European government aid was crucial to avoid market collapse,” Ušackas explained. “Even legacy carriers would have not been able to survive the COVID-induced crisis in aviation.”

“Nevertheless, the increased role of national governments in national carriers in Europe requires additional attention. Looking from the market and level playing field competition perspective, one may strongly argue that such a massive financial intervention by the governments was disproportionate and eventually disrupted competition in the European market. For example, the French government gave a historic €7.5 billion COVID aid package to Air France-KLM. Lufthansa (LHAB) (LHA) received a €9 billion aid package from the German government, while SAS, another legacy carrier in Europe, got support from both Swedish and Danish governments of €324 million (3.5 billion Swedish krona). IAG accessed almost €346 million (£300 million) from the UK government in 2020,” Ušackas continued.

However, a combination of deep financial problems, personnel shortages, and pilot strikes, have led to airline restructurings, in the case of Scandinavian Airlines (SAS), which voluntarily filed for ‘Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings’ on July 5, 2022, in the United States as part of a restructuring plan.

For Usackas, it is anticipated that looking at the cost-effective measures implemented by low-cost players, legacy carriers will increase their adoption of ACMI (Aircraft, Crew, Maintenance and Insurance or wet lease) arrangements to address seasonal demand.

“Under an ACMI arrangement, the airline (AOC holder) can outsource the required capacity (aircraft) at agreed fixed rates and can place its logo on aircraft liveries. An ACMI contract allows an Airline (Lessee) to circumvent the need for in-house financial and human resources related to aircraft maintenance, continuing airworthy support, crew and staff training, spare parts, and all other operational matters. The main advantage of ACMI is the mutually agreed fixed costs of operating aircraft per month and season. A local airline (AOC holder) is less likely to face operational surprises while a smooth operation is guaranteed. The Lufthansa Group, for example, has increased the number of its ACMI leased aircraft to satisfy the 2022 summer demand. According to preliminary estimates by utilizing 10% of ACMI as seasonal capacity, the airline yield can increase from 1,57% to as much as 12%,” highlighted Usackas.

“What’s clearly happening is we have the French and the Germans creating a huge fund — billions of state aid — that will allow them to either low-cost sell against the likes of Ryanair during the recovery period or allow them to engage in mergers and acquisitions and buy up all their weaker competitors when this is over.” – Michael O’Leary, Ryanair CEO

Has state aid been offered at the cost of competition and mid-sized carriers?

In May 2020, Ryanair’s CEO Michael O’Leary argued that government-backed support packages received by the EU’s airlines had potentially distorted competition and increased the possibility of larger carriers absorbing weaker competitors.

In an interview with Euronews, O’Leary said: “What’s clearly happening is we have the French and the Germans creating a huge fund — billions of state aid — that will allow them to either low-cost sell against the likes of Ryanair during the recovery period or allow them to engage in mergers and acquisitions and buy up all their weaker competitors when this is over.”

However, before the pandemic, Ryanair’s boss predicted that up to 80% of European air traffic would be controlled by five airline groups within five years from 2019, namely Lufthansa (LHAB) (LHA), IAG, Air France-KLM, Ryanair and EasyJet.

O’Leary also forecasted that mid-sized carriers such as Norwegian, TAP Air Portugal and Alitalia (now ITA Airways) would likely be absorbed by the five airline groups.

Lufthansa (LHAB) (LHA) and its partner Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) are currently mulling a combined 80% stake in Alitalia’s successor, ITA Airways. Lufthansa (LHAB) (LHA) aims to acquire a 20% stake while MSC eyes a 60% share.

Other parties have also shown interest in acquiring ITA Airways, namely Delta and Air France-KLM, with support from US fund Certares, and low-cost carrier investor Indigo Partners.

However, while we might see one of a few smaller-size carriers merging with some of the larger carriers, the European airline industry and market are very unlikely to turn into a full-blown oligopoly, according to Ušackas.

“As long as legacy carriers continue to depend on the government’s support, attempt to improve cost-effectiveness, and focus on repaying the loans received during the pandemic, it is unlikely to see their efforts to absorb smaller European carriers,” he added.

Will European LLCs consolidate?

The idea that Europe’s LLCs might merge was proposed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021 Wizz Air approached easyJet with a takeover offer, however, the British low-cost carrier refused the bid. Had the deal continued, a fully continental airline network combining Wizz Air’s network in Central and Eastern Europe with easyJet’s market share in Western Europe could have been established, Ušackas said.

“There could be some difficulties finding the right business model for such a merger. While Wizz Air is a true low-cost carrier, easyJet is more of a mid-tier airline. Therefore, some changes would need to be considered,” Ušackas added.

Similarly, Ryanair’s CEO Michael O’Leary revealed that the airline had approached Wizz Air on multiple occasions with the offer of a buyout. However, these approaches have been rebuffed.

According to Brueckner, “Ryanair carries more passengers than any other EU carrier thus, being a big player, I’m sure the regulators would not look kindly on an acquisition by it.”

Ušackas also said that while consolidation offers airlines larger market shares with the potential for quicker recovery following the pandemic, Europe’s low-cost carriers are keen to remain independent, stating that European LLCs are “unlikely to embrace consolidation any time soon”.

In contrast, the US has embraced further airline consolidation as a new bidding war is currently playing out between low-cost rivals JetBlue Airways and Frontier Airlines as they compete to acquire ultra-low-cost airline Spirit Airlines (S64) (SAVE).