As the sole natural satellite of the Earth, the Moon has always been a key part of space exploration, offering immense potential for scientific discovery.

The initial race to land on the Moon, motivated by ideological and national pride during the Cold War, has evolved into today’s quest for lunar water.

Since the first human-made object reached the Moon on September 13, 1959, namely the Soviet Luna 2 lander, it is estimated that more than 3,000 spacecraft have landed on the lunar surface.

While the history of humanity’s journey to the Moon is well documented, the aftermath of these lunar trips, particularly what was left behind on the Moon’s surface, is a lesser-known story.

While countries have competed to place their flags on the Moon, a legacy of debris was also left behind.

According to NASA, humans have left approximately 500,000 pounds (more than 225,000 kilograms) of refuse on the Moon.

While there have been only nine manned lunar missions so far, has humanity already begun to pollute its nearest celestial neighbor?

Lunar rocks over space boots

Apollo 11 achieved a huge milestone in space exploration on July 20, 1969, when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first people to walk on the Moon.

But alongside accomplishing this historic feat, the crew also left a number of items behind on the lunar surface. Among these were personal belongings and objects related to the mission.

Some were left intentionally for scientific purposes, but others, such as boots and gloves, were simply deemed ‘non-essential’ for the return flight. A Hasselblad 500E camera used to document the historic first manned lunar mission was left behind, with only the film magazines, which contained invaluable images, being brought back to Earth.

Leaving these items behind was a practical decision to allow for the return of collected lunar rock samples and meet the requisite weight restrictions for the flight back home.

Several of the Apollo missions that were undertaken between the late 1960s and early 1970s left cameras and geological instruments behind, plus a total of 16 pairs of space boots. What’s more, the Apollo crews left nearly 100 bags of human waste, including urine, feces and vomit, as well as a pile of used wet wipes, on the lunar surface.

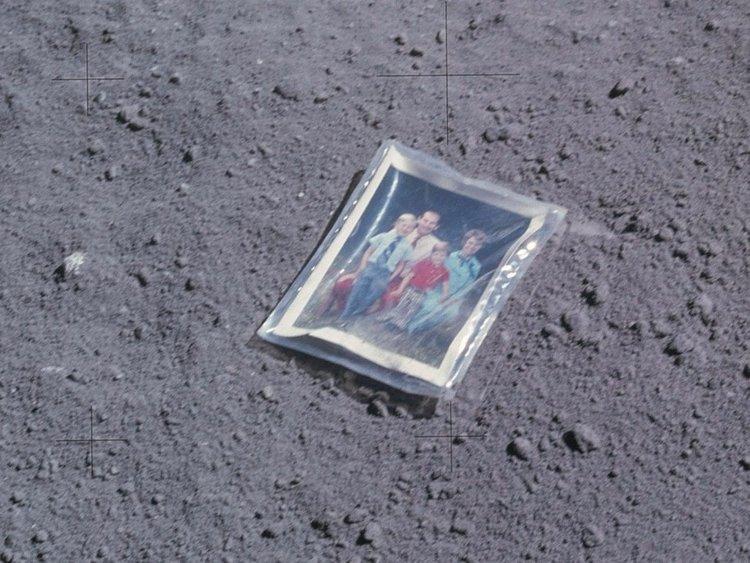

The family photo that was left on the surface of the Moon

While bags of human waste are not exactly representative of humanity’s romanticized relationship with the Moon, other items that have been left there feel more fitting.

The ashes of Eugene Shoemaker, a renowned planetary geologist, were taken to the Moon aboard the Lunar Prospector mission in 1998. This made Shoemaker the first (and so far, only) human to have his remains sent to the Moon.

The capsule containing the ashes was inscribed with a passage from Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare:

“And, when he shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night,

And pay no worship to the garish sun.”

In fact, five of the six Apollo missions that landed on the Moon left plaques bearing inscriptions (Apollo 12 was the exception, and only failed to do so due to simple forgetfulness).

The Apollo 11 plaque read: ‘Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.’

The first manned Moon landing mission also left behind a golden olive branch as a symbol of peace.

Additionally, astronaut Charles Duke of the Apollo 16 crew left behind a photograph of himself and his family: his wife Dotty and his two sons Charles and Tom. It was framed, inscribed by Duke and tucked into a plastic sleeve before being left behind on the lunar surface.

The inscription on the back of the picture read: ‘This is the family of astronaut Charlie Duke from planet Earth who landed on the moon on April 20, 1972’. However, due to the harsh environment of the lunar surface, it’s likely that Duke’s family photo has now degraded significantly.

Testing the grounds

The Apollo astronauts studied the Moon’s environment using various scientific instruments, some of which they left behind intentionally.

During the Apollo 14 mission of early 1971, astronaut Alan Shepard used a lunar soil sampling scoop handle and a 6-iron head to create a makeshift golf club. Famously, he used this club to hit two golf balls across the Moon’s surface.

Several months later, in July 1971, Apollo 15 commander David Scott performed a live demonstration for the television cameras. Inspired by Galileo Galilei’s theory, it showed that in the absence of air resistance, a geologic hammer and a falcon feather would fall at the same rate and hit the ground simultaneously.

This principle was illustrated further when all six US flags planted during the Apollo missions remained still, underscoring the Moon’s lack of a significant atmosphere and the absence of wind or air movement.

The flags, along with the golf club, balls, feather and even the hammer, were all abandoned, adding to the debris and clutter on the lunar surface

Spacecraft burial

The United States is not the only contributor to the Moon’s collection of man-made debris. Notably, in 1959, the Soviet Union’s Luna 2 mission ended with a crash landing, leaving behind a pennant displaying the State Emblem of the Soviet Union and some scattered wreckage.

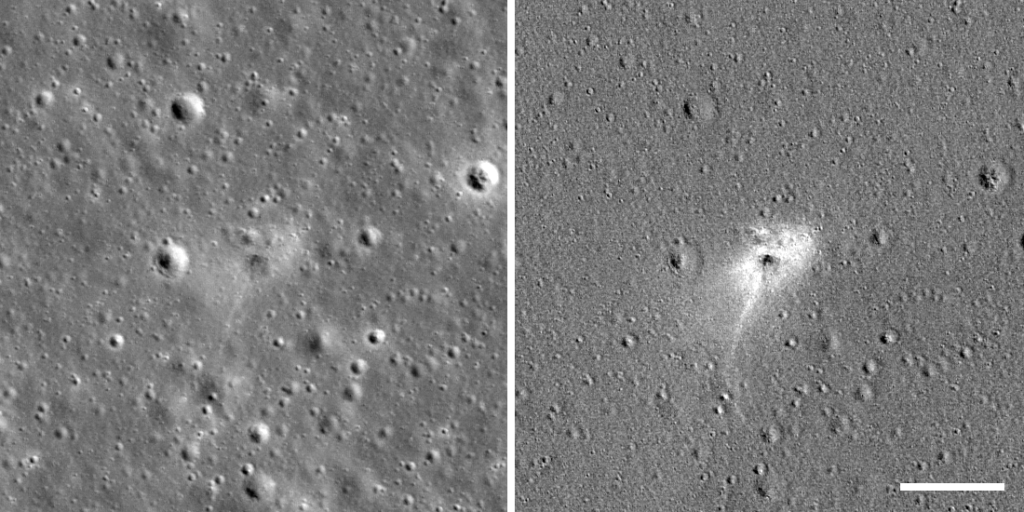

In August 2023, Russia’s Luna-25 probe also met an untimely end when it crashed into the Moon’s surface, adding to the growing pile of refuse.

Over the decades, several nations have contributed to the Moon’s collection of trash:

- China’s Chang’e missions of the 2010s deployed both landers and rovers, which remain on the Moon to this day.

- In 2019 India’s Chandrayaan-2 left debris following an unsuccessful landing.

- Also in 2019, Israel’s Beresheet probe crashed during its landing attempt leaving behind the wreckage.

- The European Space Agency (ESA) made a deliberate decision to crash its SMART-1 probe in 2006 after launching it in 2003, leaving wreckage behind.

- Japan’s lunar missions in the 1990s and 2000s added to the pile yet further, leaving their spacecraft as additional debris.

Combined, the Moon’s surface now contains debris from more than 50 crash landings, including various spacecraft components such as rocket boosters and discarded lunar modules.

Moon’s ice vs. lander emissions

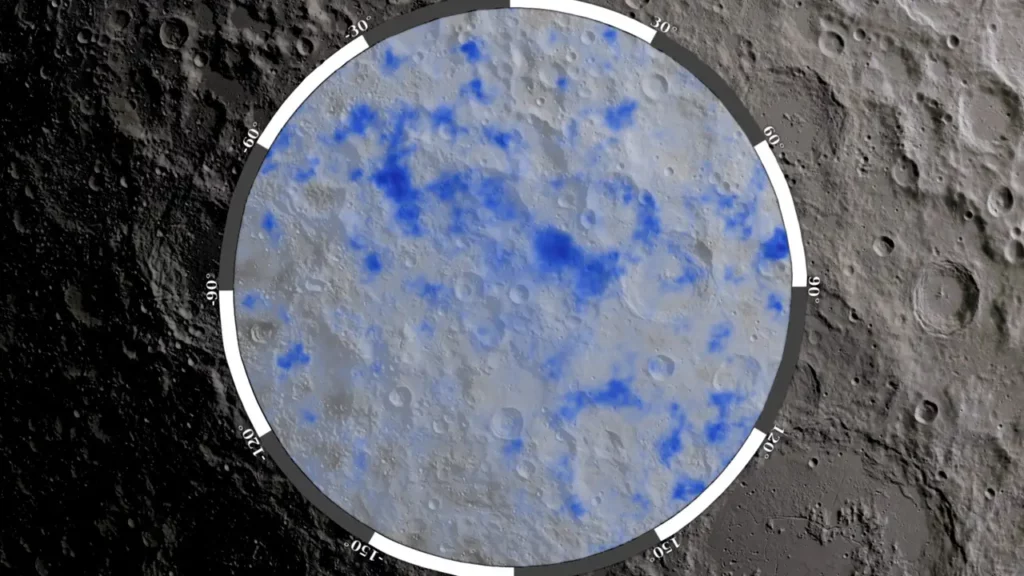

Another significant concern regarding the negative impact of humans on the Moon is the exhaust fumes from lunar landers that quickly disperse across the surface, potentially contaminating ice at the lunar poles, which is of huge scientific importance.

A study published in August 2020 by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory highlighted this issue, demonstrating through simulations that water vapor emitted by a lunar lander could spread around the entire Moon within a few hours. Remarkably, a substantial portion of this vapor can persist on the lunar surface and in the atmosphere for up to two months, with about 20% freezing out by the poles a few months later.

This pollution has implications for studying the native ice in the Moon’s poleward craters, as it could prevent accurate measurements of lunar ice, impacting the understanding of water’s origin and dispersal in the inner solar system.

The balance between lunar exploration and preservation

The Moon’s surface is still considered to be sterile due to its harsh environmental conditions, including extreme temperature fluctuations and exposure to solar and cosmic radiation which are inhospitable to Earth’s microbes.

However, the questions of whether the human waste left behind from lunar missions has introduced bacteria to the Moon’s surface, or any of those bacteria could survive in harsh lunar conditions, are complex issues that researchers continue to explore as we learn more about Earth’s sole natural satellite.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 established that the Moon and other celestial bodies are for peaceful use by all countries, but it does not explicitly address the debris or objects left behind following space missions. While it mandates nations to avoid harmful contamination of space and celestial bodies, there are no detailed guidelines on managing or cleaning up space debris.

To mitigate pollution, certain policies and directives have been introduced by space organizations. NASA, for instance, has instigated new policies to protect the Moon and Mars from contamination as human spaceflight advances. These policies are encapsulated in two NASA Interim Directives released to address planetary protection for missions to the Moon and Mars, reflecting recommendations from an independent review board.

Furthermore, the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) panel on planetary protection is responsible for formulating and updating policies concerning planetary protection issues, which could encompass pollution on the Moon.

As lunar exploration intensifies, with various national programs and private companies eyeing the Moon for scientific research, mineral extraction and potential colonization, the importance of preventing pollution on the lunar surface has grown.

In May 2023, a ‘Fair and sustainable use of space’ policy document addressing the sustainable development of space activities was created by the Council of European Union, indicating a move towards more responsible practices in lunar exploration.

These measures indicate a growing recognition of the problem of pollution on the Moon, and a concerted effort towards establishing guidelines and policies to mitigate this issue. This should ensure that the quest for lunar exploration does not come at a serious cost to the Moon’s scientific and natural value.